Opening Hours

Tuesday to Friday 12:00-20:00 (Last admission: 19:30)

Saturday and Sunday 12:00-21:00 (Last admission: 20:30)

Closed on Mondays

The Train Garden is open to the public every day

Tuesday to Friday 12:00-20:00 (Last admission: 19:30)

Saturday and Sunday 12:00-21:00 (Last admission: 20:30)

Closed on Mondays

The Train Garden is open to the public every day

111 Ruining Road, Xuhui District, Shanghai

021-33632872

info@startmuseum.com

“The princess’s servants brought her two mirrors. One was fast and the other slow. Whatever the fast mirror picked up, reflecting the world like an advance on the future, the slow mirror returned, settling the debt of the former. When they brought the mirrors to Princess Ateh, she saw herself in the mirrors with closed lids and died instantly.” This is a fragment from the Dictionary of the Khazars on the “fast mirror” and the “slow mirror”. Princess Ateh has letters written on her left and right eyelids, letters chosen from the Khazars’ poisonous spell, which will kill anyone who sees them. Looking into the fast and slow mirror, she sees the letters on her face that she would never have had the chance to see. She died, and killed between the past and the future.

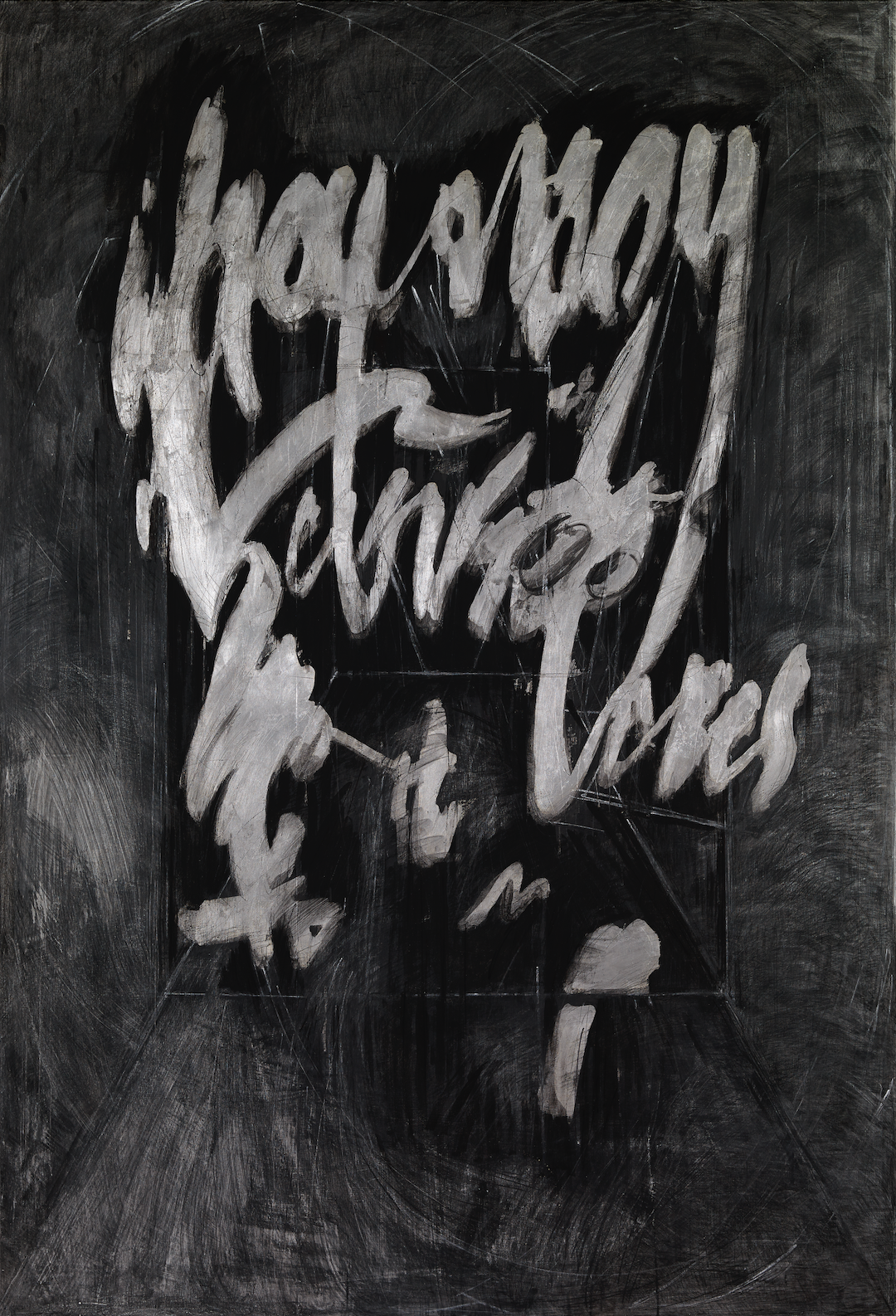

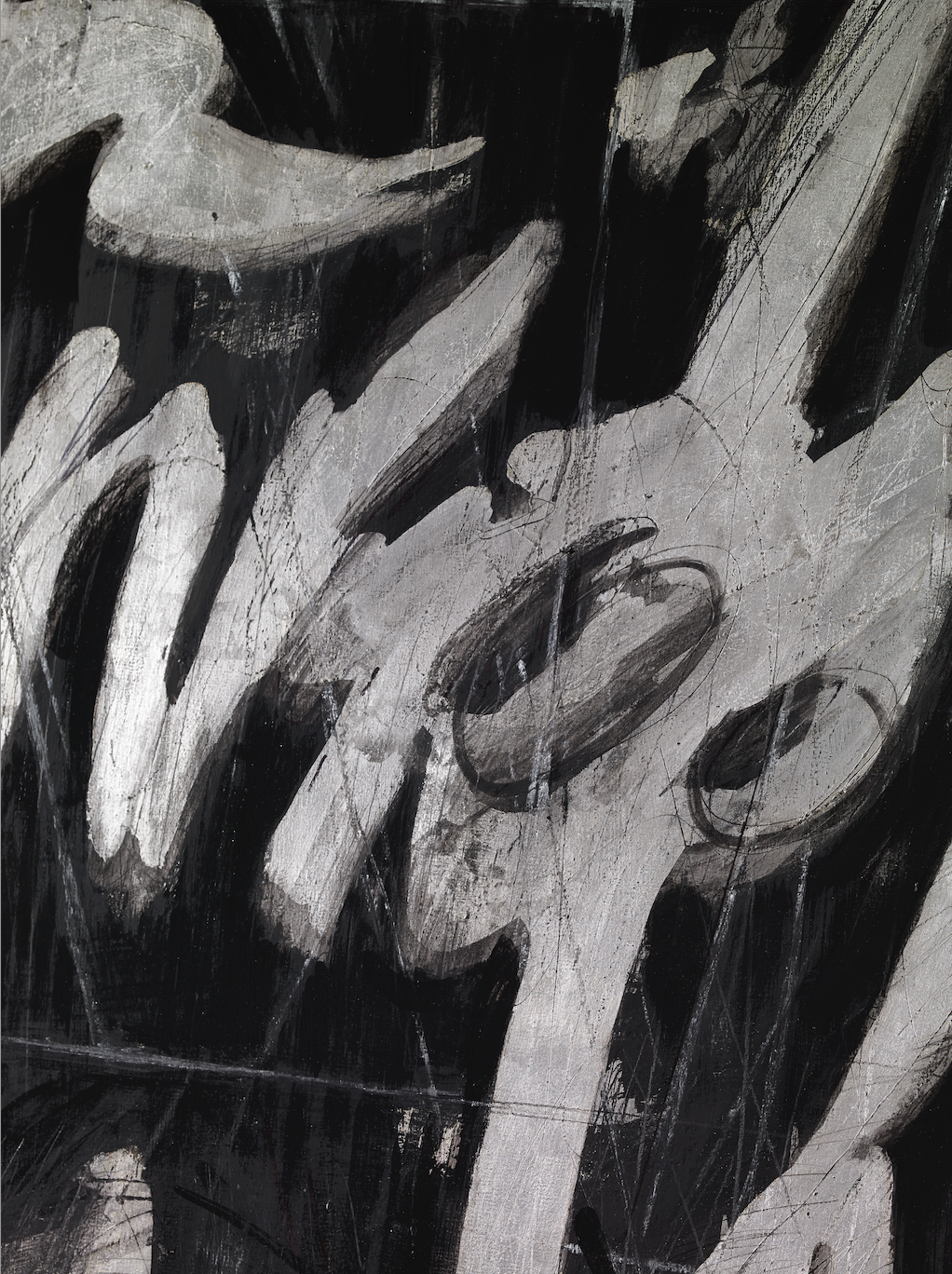

Eternity and nihility overlap in a cycle of infinite; time is not real, death is not the end but perhaps also the beginning, it is the perception within the artist’s consciousness and her “Self”. The story of the Dictionary of the Khazars may help us to enter Wu Di’s “Amber” space, the scene of the exhibition “Romantic Language”: the glass walls of the exhibition hall are covered with amber PVC, which plunges the space into a eternal twilight; silver text is repeatedly written on a black painted wood board, as if stirred by a strong wind, the exact meaning of which cannot be discerned; and the same content is repeated in several sketches; gold-toned installations follow with strange orange light. This is Wu Di’s frozen space, her soft science fiction, where she unconsciously invades the viewer’s consciousness with “repetition”, “circularity”, “time”, “nihility”, “death” and “romance”. Meanwhile, under the continuous reading of the exhibition space, our memories are repeated, forming circuits.

From her early work, Wu Di reveals a unique perspective of seeing the world – a transcendent, deeper sense of self and environment. Beyond that, she mimics the early paintings of the Renaissance and uses mysticism, religion and mathematical formulas to express the darker, conscious dimensional forces of human nature. In the “Descent from the Cross” series that influenced her the most, she covered up “the descent from the cross” of classical painting, collaged it and rewrote it, presenting personal beliefs and extreme emotions. In Compound Eye No.2 (2015), the artist uses a fascinating variation of mathematical formulas, in which the compound eye gazes at the viewer as if it were gazing at the artist’s own reality. In Female and Male No.1-9 (2008), each of the nine species is painted on a background graphic with bee symbols. Humans, as well as the rest of the species, the stories about their vitality and sacrifice are growing endlessly.

Compared to Wu Di’s previous and recent exhibitions, the exhibition of Genealogy Study of Artists “Romantic Language” is lighter, like a deer popping up in the woods or a World Tarot card. This exhibition can be described as a turning point in her artistic language or a large experiment in space. As entering the main space, people will see three paintings from “Romantic Language” series, which shares the same name with the exhibition. These are paintings of “words”. There are some silvery white scratches on the dark background, and the interplay of colour and brushstrokes reveals a blurred texture. Such texture flows across the canvas, giving the painting a wandering or even an unreal appearance. On closer inspection of the painting, Wu Di has repeatedly scribbled the letter in such a way that its true meaning is no longer discernible. She is vigilant about language, contrary to her perceptive side. Language itself carries strong pointers, forms and matrices that people take for granted. It is what Erwin Panofsky mentioned that “By elucidating the text and linking it to the symbolic values prevalent in the established culture, the image is transformed into a symbolic system”. And Wu Di is instinctive, blurring the symbolic text to its essential outline. This ambiguity does not demand any kind of certain answer, but only thinking, constant thinking. And in the process of overlapping, the overwhelming sense of contradiction is pushed to its highest climax – one is reminded of the poetic yet confusing title, “Romantic Language”, and perhaps, we can feel language, and everything, romantically.

Standing in front of the wall next to the stair, the same text as before reappears (several almost identical sketches hang on the wall). The strong sense of dislocation is transformed into a gentle force that knocks us out from the frozen space. To look around and moves the body frozen in amber, as if there are something indefinable exists silently in the space, they are the “invisible” things that Wu Di’s work brings out. In the past, it might be some mysterious painted creatures. In this exhibition, it is the perception of time in her Self, a ritual about time.

In medieval times, the image of “time” was corresponded to a certain planet, associated with mythology and astrology, leading to the intention of aging, poverty and death. Does the darkness from Wu Di’s work have anything to do with this death? And what is time? Does it exist, and how do we define and feel it? “And if time is not real, then the gap which seems to be between the world and the eternity, between suffering and blissfulness, between evil and good, is also a deception.” Wu Di mentions Siddhartha. There is a vital river in Hesse’s novel, which symbolises the Self, the nature of the Self, and so as the enlightenment. The river has witnessed to his search for the true state of the Self, the spirit of Hinduism, and the embodiment of Brahma. Also, the sadness and darkness contained in time itself become part of the amber in “Romantic Language”. The past and the future, our memories, obsessions, pain, love and happiness, all become a kind of reciprocation. Everything seems to become nothingness, but she is not afraid of it.

Two installations in the space reveal another side of her rebelliousness, the main body of Feel Good (2015) is a block of wood split into double branches, with a bundle of blonde wigs placed in the middle. The ambiguous hair, shaped like a horseshoe, is more of an attempt at ambiguity than eroticism. You Sister (2013) is an intervention of personal experience, with a teeth model carefully arranged in a cake tray on a golden trolley and the word ‘you sister’ drew inside of the mouth. This represents the power of rock and hip-hop in Wu Di’s work, the unique romance and persistence of children who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, the golden age of Chinese rock. In her first two solo exhibitions, “AMEISE, AMEISE” and “BABY, DON’T CRY”, similar violence and eroticism can be felt, even accompanied by a monumental sense of resilience, a unique feminine beauty and strength.

Artists are rarely labelled as “female” or “male”, which is strongly indicative and sample-like. As feminism evolves to a de-feminine, neutral or even masculine status, does the innate female perception, the sensitive and poetic part, become a trait that should be discarded? Wu Di, with her clear, honest, complex and mysterious works, reveals the part of her that belongs to women; the beauty that abounds in the space is a manifestation of a female artist, and is also a natural artistic expression. Whereas Carl Gustav Jung drew on alchemy to analyse the inner relationships of the human mind, Wu Di connects the inner perception with the external world through painting. Detaching herself from normal rules of universal context, Wu Di leaves her soul in a hazy state, rather than a definite meaning, and she completes the groping and advancement of her own river. This is her attitude towards to the world, which makes her works overflow with the energy of life, an energy that allows her perceptions to connect to the world without being limited to the role and description of human beings themselves.

Whether species, androgyny, religion or the frozen space of cycle, the inspiration and revelation from Wu Di’s works, would makes the spirituality of living beings transcend materiality. And perhaps, this is a way to open up new pathways.